How the City of London allowed the consultation on the ponds to be hijacked

The day before the announcement of the permissions judgment in our case against the City of London over the Hampstead Ponds, the corporation rushed out the results of its consultation exercise, saying:

“A clear majority (86%) of respondents said the ponds should continue to operate as trans‑inclusive spaces, with trans men using the Men’s Pond and trans women using the Ladies’ Pond.”

The consultation was open online from 30th September to 25th November 2025. It received 38,742 responses: 31,296 claimed they swam in the ponds. This is an extraordinary number, which demands some reality checking.

For comparison, this survey got 35 times more responses than the City got in 2020/21 when it did a survey of swimmers’ experience of Covid adaptations. A link to that questionnaire was sent to nearly 11,000 people who had used the Eventbrite booking platform for the ponds. It got 1,108 responses. The same year the Kenwood Ladies’ Pond Association did a survey concerning the impact of changes in the charging policy at the ponds and 600 people responded. A survey of swimmers in 2021/22 got 2,079 responses.

At a meeting of the Hampstead Heath Consultative Committee on 13th January 2026, one of the members, Simon Hunt, commented on the large number of responses:

“I am not sure there are 40,000 people on the Heath who replied. I was a little concerned that the replies might reflect a population other than the ones who use the Heath… Who are these 40,000?”

Andrew Impey, the corporation’s deputy director of natural environment, admitted that the City of London had anticipated that the survey might be hijacked:

“We were probably expecting nearer 100,000.”

“We knew there was the potential for it to get hijacked… There will be some within those 40,000 who don’t know where Hampstead Heath is.”

Is the survey report credible?

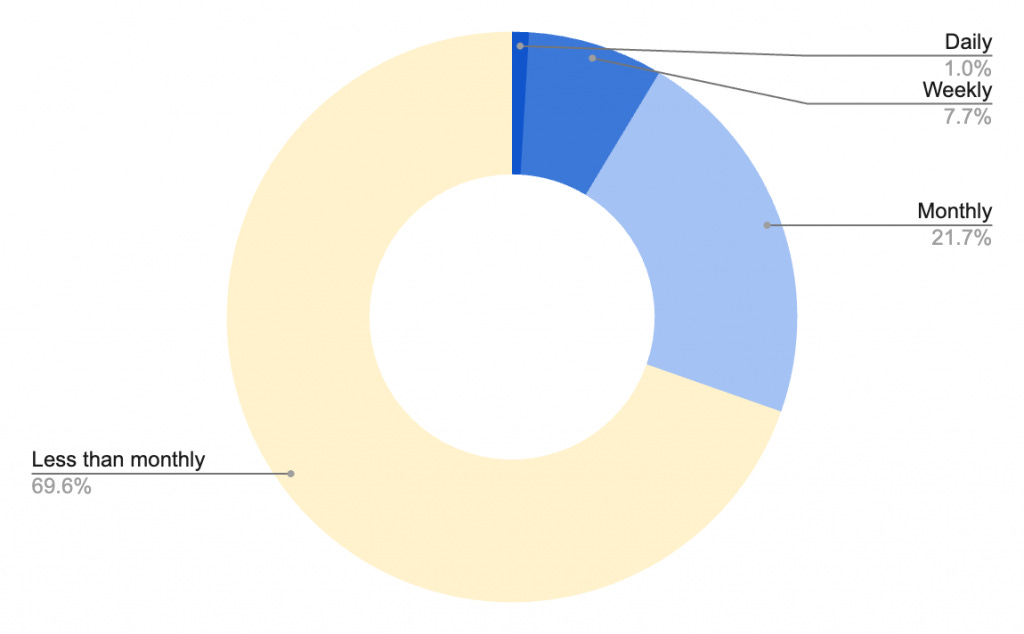

31,296 people who responded to the survey claimed to have swum in the Hampstead Heath bathing ponds and 20,821 said they had swum there within the last three months. The majority of those who responded said they swim less frequently than once a month.

66% said they had (at any time) swum in the ladies’ pond, 22% had swum in the men’s pond and 49% in the mixed pond.

How confident can the City of London be that the 31,296 people who said they swim in the ponds really do?

Simon Hunt asked a very good question and did not get an adequate response.

The Hampstead Ponds have a maximum bather load for each pond of 100 people in the water. Over the course of a year there are around 368,000 swims in total across the three ponds (based on an annual report for 2022/23). The men’s and ladies’ ponds are open all year round – for around 12 hours a day through the summer and seven hours from late October till May. The peak months are June, July and August.

Respondents who said in the consultation that they had swum in the past three months are claiming to have swum during July, August, September, October and November (depending on when they completed the survey) – five months (152 days), so we can estimate the number of swims this represents.

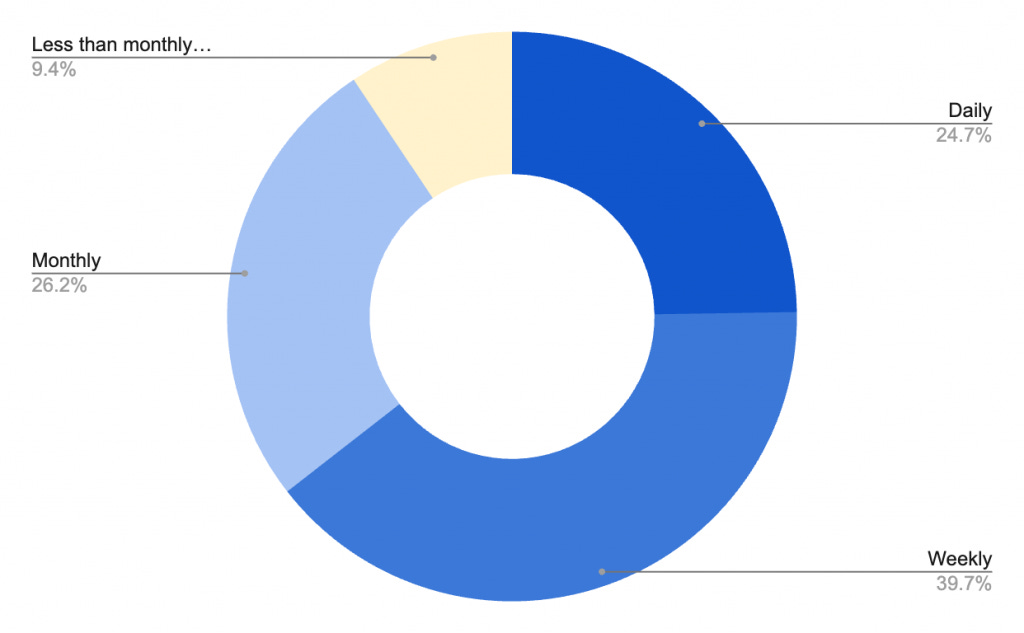

Based on these estimates we can see that the vast majority (an estimated 90%) of swims represented by survey respondents are accounted for by those claiming to be regular swimmers.

The total number of swims represented by the survey respondents would account for more than a third of the annual swims undertaken at the ponds during the year. This is an extraordinarily high response rate.

If we assume that 70% of annual swims take place during the July to November period, which covers two of the busiest months, around half of the people who swam in the ponds during those five months would have undertaken the survey.

This is implausible, but when combined with the demographic skew, it becomes impossible.

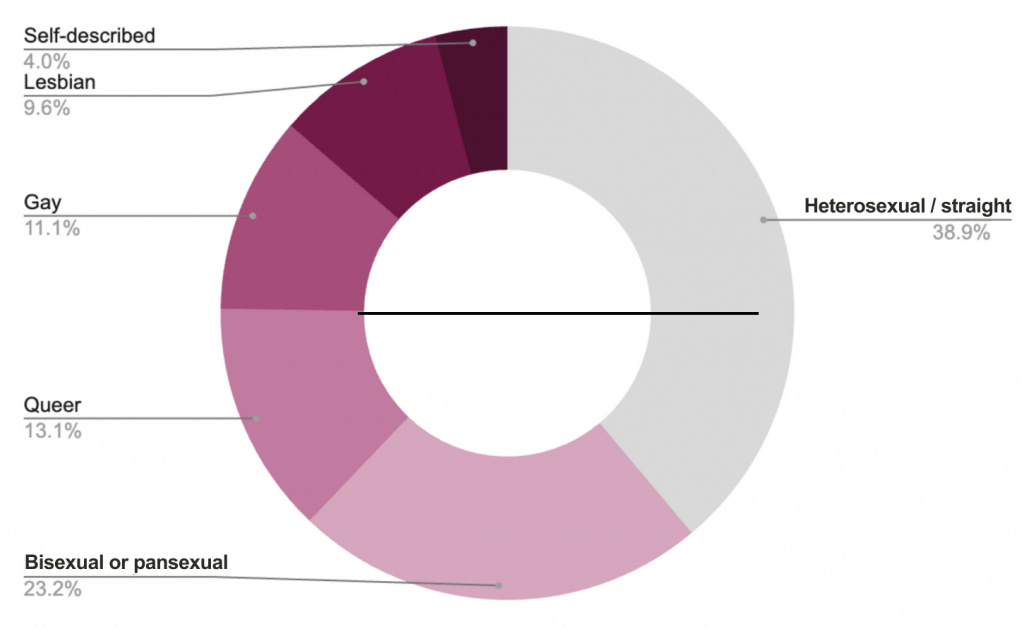

One thing that is striking about the people who responded is how many were “LGBQ+”.

In the UK census, 4.7% of the population said they were LGB. So if there are 368,000 swims a year, you would expect about 17,400 swims by LGB people over the year. Yet if the consultation responses are accurate, they suggest that over just five months of the year, 77,600 swims by LGB people took place. That would be around 450% of the expected number of swims by LGB people over the course of the entire year. The only plausible explanation is that a large number of the consultation responses are not accurate.

The survey was undertaken by Tonic, an independent social research organisation specialising in public consultations.The methodology section of its report does not say how the survey was promoted or distributed. Tonic says:

“Participation in the consultation was on a self-selecting basis. The findings in the report, therefore, carry the unavoidable risk of self-selection bias and are, therefore, not generalisable to the overall population.”

This is not an accurate description of the situation. The demographic skew in the data shows that there is no mere “risk” of self-selection bias: it is certain that this occurred and that it has dramatically biased the sample. The results are not merely unrepresentative; there is strong evidence that the survey was hijacked.

This was not, as Tonic claims, unavoidable. The City of London could have controlled the survey so that only people who had genuinely used the ponds could have claimed to be pond users – by providing a personalised login code to those who had booked via the Eventbrite system or had season tickets, for example. It could have provided a separate survey for non-pond users and advertised it with QR codes around the heath. It chose not to do that.

The aim of the consultation should have been to gather data that was as representative as possible of the views of the user base of the ponds, and of the potential user base of people who use the Heath. If they do not do this, the findings are worthless.

The consultation leaves the corporation knowing no more than it did before it undertook the survey: some people feel strongly that men who identify as women should be able to access services for women and girls, including where they are naked or undressing, and some people do not.

The central issue regarding the use of the ponds is this: on what objective criterion are sex-segregated spaces based?

Sex segregation in changing rooms and intimate spaces did not arise as an arbitrary cultural gesture, but as a preventive measure grounded in an empirical reality: the vast majority of crimes, including sexual offences and indecent exposure, are committed by males, regardless of how they perceive or identify themselves. Is this fact irrelevant to those who defend self-identification as the sole criterion?

Acknowledging this does not turn all men into suspects, just as locking one’s front door does not mean considering the entire neighborhood criminal. It is a general rule based on risk categories, not on individual moral judgments.

For that reason, this is not a matter of arbitrary “discrimination,” but of functional segregation. All men are excluded from women’s changing rooms, and this exclusion is not experienced as a denial of dignity, but as a structural norm aimed at protecting women’s privacy and safety.

The stigma argument is therefore inadequate. That trans people experience discrimination is a real problem, but it is not solved by dismantling criteria designed to protect the rights of others. One injustice is not corrected by ignoring another. The association between male sex and higher rates of offending is not a moral prejudice, but a statistical fact underpinning preventive policies.

Trans people who identify as women may exercise broad personal freedoms, but like any right, those freedoms have limits when they come into conflict with the rights of others, especially in contexts involving privacy and bodily intimacy.

When sex as a criterion is replaced by self-identification, the preventive foundation becomes uncertain. If merely declaring oneself a woman is sufficient to access a female space, the boundary ceases to be objective and verifiable. The common response—“action will be taken if someone behaves inappropriately”—does not resolve the issue, because the purpose of segregation is to reduce opportunities for harm before it occurs, not to intervene afterward.

In this context, the Equality Act 2010 is crucial. The Act provides for exceptions for single-sex services where they constitute a proportionate means of achieving legitimate aims such as privacy, decency, and safety. In other words, the legislature explicitly recognized that tensions between rights may arise and that, in certain contexts, protection based on biological sex may be justified. If in practice that exception is neutralized by policies of unrestricted self-identification, the problem becomes one of legal coherence and of how sex is defined in law.

Nor is it convincing to reduce all concerns about safety to mere “stigma.” Recognizing real conflicts does not amount to denying anyone’s dignity. The question is which criterion best preserves the original function of these spaces.

Ultimately, the debate is not about inclusion versus exclusion in the abstract, but about two principles that can come into tension: subjective identity and sex as a legal and material category. If the law provides exceptions to protect female spaces, the legitimate question is when and how they should be applied. Avoiding that discussion by appealing solely to self-identification does not seem sufficient.

For that reason, my position is clear: in intimate spaces involving shared nudity, the relevant criterion should remain biological sex. Not out of hostility toward anyone, but because it is the only objective, verifiable criterion consistent with the preventive purpose of such spaces.

Moreover, Hampstead Heath has facilities for men, for women, and a mixed area. This is not a situation requiring major structural reform, but rather a decision about which criterion should govern each space.

The consultation is meaningless. The law is clear. Even if 100% of respondents wanted men in the ladies pond it really doesn’t matter and holds no weight.

You must fight on