What will 2026 bring for sex-based rights?

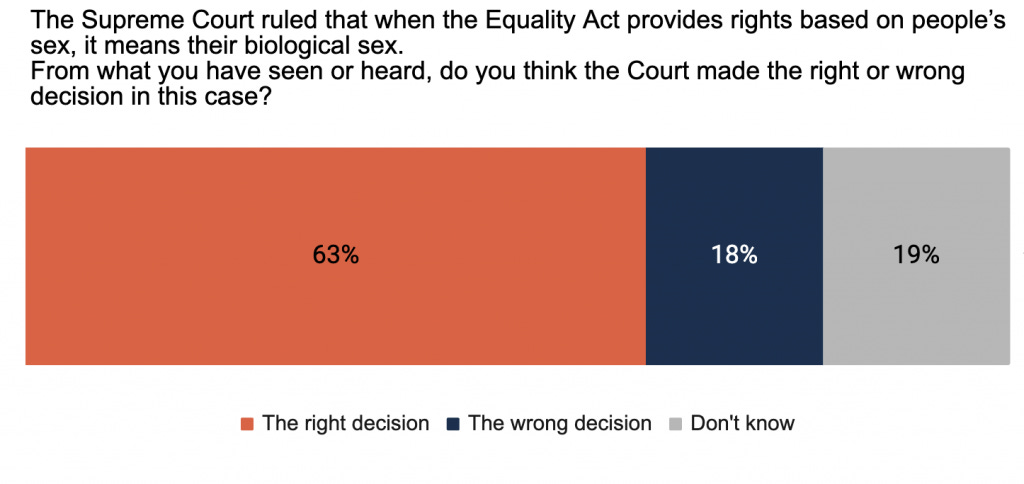

The Supreme Court judgment on the meaning of sex in the Equality Act brought legal clarity to sex-based rights last year, and most people agree with it.

The judgment should have ended years of confusion. Instead, businesses, charities and public bodies that have been operating outside the law have revealed themselves as resistant to change, and them and their regulators as reluctant to stand up against gender ideology.

2026 will be a year of holding institutions to account. If the government, public bodies, regulators and courts are not willing to implement the law, compliance must come through scrutiny, advocacy and litigation.

At the same time it is a year for positive action, built on the recognition that when organisations do things for women, this is a group defined by sex.

Three big themes will shape our campaigning in 2026: making the Equality Act work, preventing harm in medicine and education, and ensuring that policies and organisations directed at meeting the different needs of women and men are clear about their purpose.

Making the Equality Act work – at last

Statutory guidance must align with the law

The most urgent issue at the start of the year is the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s statutory guidance on services, public functions and associations. This guidance must reflect the Supreme Court judgment and improve on the previous draft, which was legally flawed.

The government must lay the guidance before Parliament – or explain publicly why it is failing to do so.

Unless the Secretary of State, Bridget Phillipson, acts by early February to lay the guidance before Parliament she will miss the 40 “sitting days” needed before the one-year anniversary of the judgment. It will be shameful if we reach 16th April without new guidance in place.

Phillipson has said that she will publish the guidance “as soon as I can” and that she hopes to now “crack on”. We hope so too.

We expect attempts to “pray against” (debate) the guidance with pressure to undermine the law. Sex Matters will continue to press for lawful, clear, and enforceable guidance, and to challenge any attempt to dilute the meaning of sex.

Duty bearers can no longer hide

In any case all duty bearers are already required to comply with the Equality Act, as clarified by the Supreme Court. Claims that organisations are “working at pace” or “waiting for guidance” instead of changing their policies to bring them in line with the law are increasingly implausible and legally indefensible.

A wide range of institutions will have to revisit policies, practices and guidance in 2026, including regulators such as the Health and Safety Executive; the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS); the Information Commissioner’s Office; and the Charity Commission. So will the civil service, professional bodies, sports councils and local authorities.

In Northern Ireland, the Equality Commission has asked the High Court for leave to apply for judicial review to clarify how the judgment should be applied in the different legal context there.

With local elections in England and devolved elections in Scotland and Wales in May, politicians will be pressed to say whether they support lawful, sex-based protections – or continued ambiguity.

Litigation holds institutions to account

Because so many institutions refuse to act voluntarily, strategic legal action remains crucial.

Sex Matters is involved in several cases and will continue to support strategic litigation to defend the law and expose unlawful practice. We are waiting for decisions in several cases, including Good Law Project v EHRC and the permission decision on the Hampstead Ponds.

Whatever the outcomes, litigation will continue to act as a substitute for political leadership, forcing reluctant institutions to confront the law one case at a time.

“First do no harm”: medicine and education under scrutiny

“Gender medicine” is ignoring the law

Despite the Supreme Court’s clear statements, which limit the expectations of those who wish to be accepted as the opposite sex, gender medicine is carrying on regardless. At the end of last year a research ethics committee gave King’s College London the green light to begin recruiting children for the Pathways puberty blockers trial.

Campaigners and parents have already signalled their intention to seek judicial review, arguing that the trial fails to meet standards of good clinical practice.

Meanwhile, NHS England is reshaping adult gender services to accelerate assessment, transfer prescribing to GPs and funnel patients towards surgery – again, with little apparent regard for the lack of evidence of treatment efficacy and many patients’ unrealistic expectations. This was the disappointing conclusion of the Levy Review, released in December 2025.

For children and young people, NHS service specifications are due to be finalised. Yet there is scant evidence that those overseeing these changes have engaged meaningfully with the fact that other people have rights.

Will the schools guidance finally be released?

Long-awaited guidance on “gender questioning children” in schools in England is expected, alongside a significant update to Keeping Children Safe in Education following the passage of the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill.

From September 2026, updated statutory guidance on relationships, sex and health education will take effect. It warns against teaching contested beliefs as fact, and cautions schools not to present social transition as a simple solution to distress.

But it says that secondary schools must teach children the Equality Act’s protected characteristics and the “facts and the law” about sex and gender reassignment.

There will be extensive staff training and curriculum planning. The government has committed millions of pounds to teacher training and external provision, raising questions about which organisations will be entrusted with delivery – and whether past mistakes will be repeated under new branding.

“Conversion therapy” legislation back on the agenda

The government continues to promise a ban on “abusive conversion practices”, but without a clear timetable.

With devolved elections approaching, this issue is likely to re-emerge politically. Sex Matters will continue to argue for careful, evidence-based lawmaking that protects children’s welfare and freedom of belief.

Being clear about sex where sex matters

Violence against women and girls moves centre stage

The government’s strategy to halve violence against women and girls over the next decade was published at the end of last year. The language is notably grounded in sex rather than gender identity, with a strong focus on prevention, policing and support.

Investments are planned in family services, policing capability, forensic technology and statutory guidance on coercive control.

Employment law will also change: from October 2026, employers will be liable for sexual harassment (including third-party harassment) unless they have taken all reasonable steps to prevent it.

This creates both risks and opportunities. Sex Matters will argue that preventing harassment and violence requires clear sex-based rules, not the erosion of boundaries or the suppression of lawful speech.

Digital-identity decisions will lock in consequences

Digital-identity policy is moving again, with responsibility shifting to the Cabinet Office and new frameworks under development. Proposals for government-issued digital ID, expanded data sharing and a single identifier for every child in England all raise fundamental questions about how sex is recorded, amended and used across systems.

Decisions made now about how sex is recorded, changed and used in digital systems will have long-term consequences for safeguarding, data integrity and women’s rights. Once embedded, these technical decisions will be hard to reverse. Sex Matters will continue to press for accuracy, clarity and accountability.

Women’s sport in the spotlight

Women’s sport has never been more visible or successful, yet eligibility rules remain inconsistent and contested. While many major sports have restored the female category, others persist with self-identification or two-tier systems for elite and community sport.

The updated EHRC code of practice will be crucial, as will a long-anticipated new policy from the International Olympic Committee. With major events hosted in the UK in 2026, the pressure to resolve these questions fairly, and lawfully, will only increase.

The coming year will test whether institutions are willing to comply with the law – or whether they will have to be compelled to do so.