High Court rules: EHRC guidance lawful

The High Court has dismissed a legal challenge from the Good Law Project (GLP) and three anonymous claimants against the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC)’s interim guidance on single-sex services published last year.

Sex Matters intervened in support of the EHRC.

Mr Justice Swift endorsed the interim update that the EHRC published in April last year as an accurate statement of the law for employers and service providers and ruled that “transsexual persons” under the Equality Act have no right to use opposite-sex toilets or changing rooms.

The EHRC advice on the law is accurate

GLP was judged not to have standing as it lacked “sufficient interest” in the legal questions. The three anonymous claimants did have standing, and so their substantive arguments were considered. The court dismissed their claims in their entirety. It found nothing that was wrong in law about either version of the EHRC’s statement, and found that the claimants’ human rights had not been breached by being told not to use facilities provided for the opposite sex.

Alternatively GLP argued that if the EHRC were right about the law, then the Equality Act and the 1992 workplace regulations breach human rights. The court dismissed the human rights claim:

“This judgment makes absolutely clear that it is lawful for employers and service providers to provide straightforward separate-sex facilities, and that it may be unlawful indirect discrimination against women not to.”

Maya Forstater, CEO of Sex Matters, which intervened in the case, said:

“This judgment vindicates the EHRC’s swift action in publishing practical guidance in April last year, just a few weeks after the Supreme Court judgment. The law is clear. There was never any excuse for the government, public bodies, regulators, charities or businesses to delay in implementing the Supreme Court judgment.

“We are proud to have provided witness evidence to the High Court to ensure that when the judge was thinking about the black letter of the law, he was also reminded of the underlying reality of what words like privacy, decency and propriety mean in the real world for women and girls using showers, changing rooms and toilets.

“The Secretary of State should now lay the full EHRC code of practice for service providers before Parliament without further delay. The head of the civil service should withdraw its unlawful model policy and endorse the approach set out by the EHRC. Other regulators, including the Health and Safety Executive, the Care Quality Commission and the Charity Commission, should update their own guidance swiftly to make clear that separate-sex accommodation and facilities are genuinely separated by sex.”

The legal arguments

The GLP claimants argued that the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992, which require “suitable and sufficient” facilities for men and women, require employers merely to provide separate rooms with signs but not to actually restrict who uses them in practice. Mr Justice Swift said this “places form over substance” and disregards the “obvious purpose” of the workplace regulations, which was “the provision of private space for each sex for reasons of conventional decency”.

He dismissed as “unconvincing” the argument that a women’s lavatory is not required to be female-only because it might sometimes be cleaned by a man, or be used by a young boy accompanying his mother or by a man in some kind of emergency:

“Who cleans a female lavatory from time to time is a matter entirely apart from whether that lavatory remains single-sex. The ‘emergency’ example carries no weight precisely because it is an emergency – an event that is unplanned and driven by extreme circumstances. The example of the mother taking her young son to use the female lavatory is a bad example. That (and the corresponding practice for fathers and young daughters) is a common practice but is no more than a facet of ordinary parental responsibilities.”

He recognised that none of these examples are materially the same as an employer allowing men into the ladies’ toilets, changing room or showers in order to be “trans-inclusive”:

“An employer would not comply with the obligation under regulation 20 (to make sufficient provision in separate rooms containing lavatories provided for men and women, respectively) if he permitted the room for women to be used by some men and vice versa. That would go against the purpose of the regulation.”

He also dismissed the argument that expecting people to not use the wrong lavatories would place too great a burden on employers to “police” the doors or risk criminal prosecution for breach of the workplace regulations. That point, he said, was significantly overstated:

“An employer who provides the lavatories required in the rooms required, and who in good faith adopted and applied a policy that the female lavatories were available only to biological women and the male ones only available to biological men, would do what is required by the Regulations. The employees concerned would know what was expected of them.”

Following the hearing, GLP and the individual claimants had filed written submissions relying on the judgment of the Edinburgh Employment Tribunal in Kelly v Leonardo, in which Employment Judge Michelle Sutherland had taken a different view of the workplace regulations, saying that applying a biological interpretation was “unworkable” and claiming that “the biological sex of another toilet user is likely to be unknown and may be unknowable“.

Mr Justice Swift said that none of the points set out in that judgment “cause me to doubt any of the conclusions above or the meaning and effect of regulation 20”.

The claimants had also tried to argue that the terms “man” and “woman” in relation to the 1992 workplace regulations refer to the “acquired sex” of persons with a gender-recognition certificate. Here Mr Justice Swift referred directly to the Supreme Court in FWS which said that the effect of section 9(1) of the GRA “must be carefully considered” in light of the wording, context and policy of other statutes that refer to men and women. He also referred to the Supreme Court’s reasoning on communal accommodation, which provides for separate sleeping accommodation and associated sanitary facilities for reasons of “privacy and decency between the sexes”.

The judge dismissed GLP’s argument based on remarks made by Lord Justice Pill in the 2003 Court of Appeal case Croft v Royal Mail, which suggested that at some point in a person’s transition the appropriate comparator for a claim of gender-reassignment discrimination would switch from being a person of the same sex as them (comparing a “trans woman” with another man) to being a person of their target sex (comparing a “trans woman” with “another woman”).

Mr Justice Swift concluded that the notion that the relevant comparator for a claim of gender-reassignment discrimination will change cannot survive the reasoning in FWS.

The High Court endorsed the EHRC’s interpretation that Failing to provide a single-sex lavatory could comprise indirect sex discrimination against women and that Any single-sex lavatory provided will cease to be single-sex if transsexuals are permitted to use them other than in accordance with their biological sex.

The EHRC update says: “If trans women are permitted to use a single-sex female lavatory all biological males must be permitted to use that lavatory.” Mr Justice Swift accepted that it could be direct discrimination to exclude a man from the ladies’ toilets (or other services for women), but he said this would depend on the facts of the case as to whether this was “less favourable treatment”.

The EHRC guidance offers the straightforward practical advice that if you provide single-sex lavatories (or other facilities), where possible, also provide a mixed-sex facility. Mr Justice Swift saw nothing objectionable in this and said it was not contrary to any requirement in the 1992 Workplace Regulations or discrimination under the Equality Act.

The three claimants had each referred to being concerned about using unisex lavatories instead of the ones they wanted to use. Mr Justice Swift said: “I accept these concerns are sincerely held,” but said that in reality “it ought rarely, if ever, to be the case that a person using a unisex lavatory rather than an available single-sex one will ever be a matter of comment by others”. In any case, he said, workplace gossip is a fact of life that everyone can expect to bear from time to time.

No human-rights breach

The claimants argued that if the statements of law made in the interim update are correct, that gives rise to a breach of Article 8: the right to private life and personal autonomy, which includes personal identity. The claimants submitted that if the law prohibits provision of a female facility “that may also be used by trans women”, this is an unjustified interference with the claimants’ article 8 rights.

Mr Justice Swift disagreed, saying the absence of a “trans-inclusive lavatory” is not the same as no lavatory at all.

He said that “trans-inclusive lavatories” might possibly be provided consistently with the requirements of the Equality Act 2010 and the 1992 Workplace Regulations, if this was in addition to the suitable and sufficient provision for men and women. On this analysis, he said, neither the EA 2010 nor the 1992 Workplace Regulations gives rise to any necessary interference with any aspect of the claimants’ Article 8 rights. Alternatively, he said, even if the law results in prohibition of a “trans-inclusive lavatory” (as opposed to a straightforward unisex one) that interference would be capable of being justified taking into account the rights and freedoms of others.

Read the judgment and the witness statements.

The EHRC interim update

The Supreme Court ruled that in the Equality Act 2010 (the Act), ‘sex’ means biological sex. This means that, under the Act:

A ‘woman’ is a biological woman or girl (a person born female)

A ‘man’ is a biological man or boy (a person born male)

If somebody identifies as trans, they do not change sex for the purposes of the Act, even if they have a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC).

A trans woman is a biological man

A trans man is a biological woman

This judgment has implications for many organisations, including:

workplaces

services that are open to the public, such as hospitals, shops, restaurants, leisure facilities, refuges and counselling services

sporting bodies

schools

associations (groups or clubs of more than 25 people which have rules of membership)

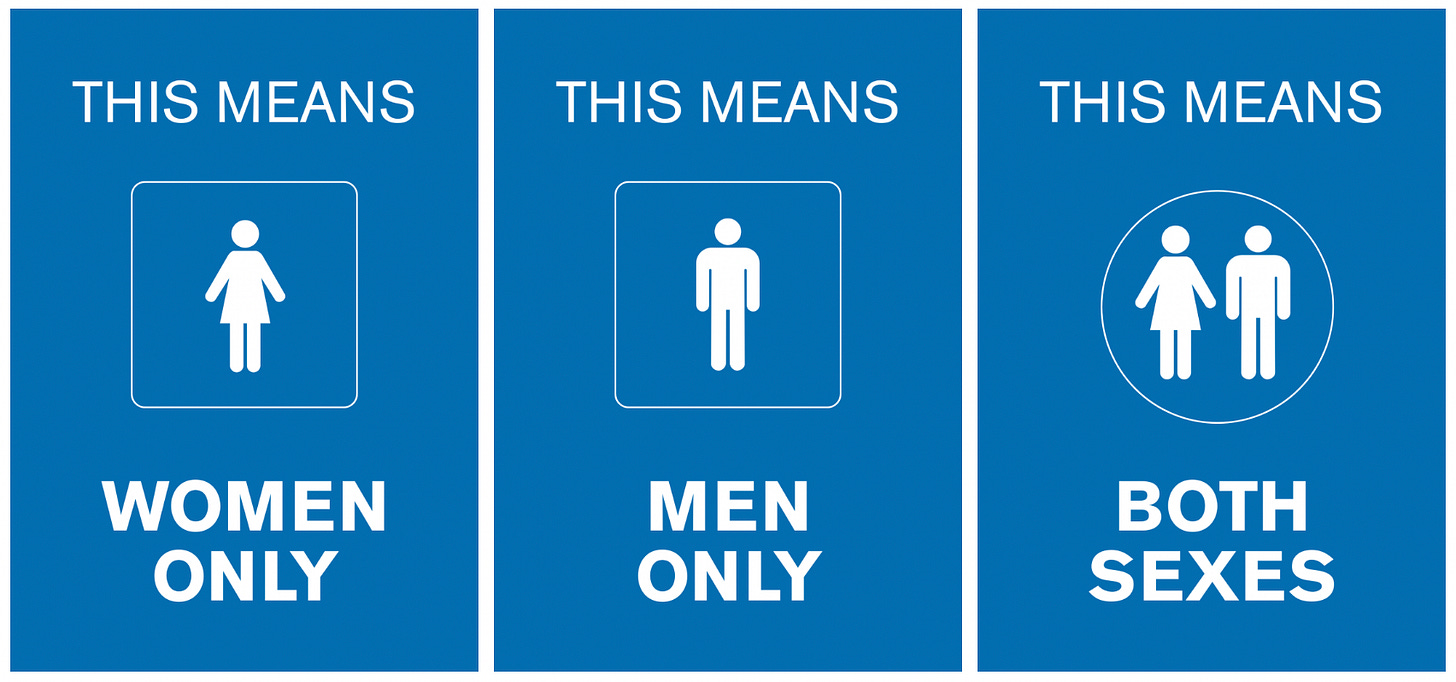

In relation to workplaces, requirements are set out in the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992. These require suitable and sufficient facilities to be provided, including toilets and sometimes changing facilities and showers. Toilets, showers and changing facilities may be mixed-sex where they are in a separate room lockable from the inside. Where changing facilities are required under the regulations, and where it is necessary for reasons of propriety, there must be separate facilities for men and women or separate use of those facilities such as separate lockable rooms.

It is not compulsory for services that are open to the public to be provided on a single-sex basis or to have single-sex facilities such as toilets. These can be single-sex if it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim and they meet other conditions in the Act. However, it could be indirect sex discrimination against women if the only provision is mixed-sex.

In workplaces and services that are open to the public where separate single-sex facilities are lawfully provided:

where possible, mixed-sex toilet, washing or changing facilities in addition to sufficient single-sex facilities should be provided

trans women (biological men) should not be permitted to use the women’s facilities and trans men (biological women) should not be permitted to use the men’s facilities, as this will mean that they are no longer single-sex facilities and must be open to all users of the opposite sex

in some circumstances the law also allows trans women (biological men) not to be permitted to use the men’s facilities, and trans men (biological woman) not to be permitted to use the women’s facilities

however where facilities are available to both men and women, trans people should not be put in a position where there are no facilities for them to use.

Fantastic, and thank you for this essay, which offers a brilliant model of analysis and advocacy.

Well done. Does this help the Sandie Peggie appeal?